About us

This Project is a mainly Y-DNA based project to investigate the origins and spread of the Ó Cléirigh group of surnames around Ireland and beyond from medieval times to the present day. As the Project is hosted on the FTDNA platform, it is necessary to take a FTDNA test to join it. You are welcome to join if:

- Your surname is Cleary or one of its variants, or Clarke with Irish origins.

- Your surname is not Cleary (etc.) but in a Y DNA test you have a close match to people who are and you think this may be a surname of your Y line ancestors.

- Your surname is not Cleary (etc.) but your recent ancestors were Cleary (etc.) and you are researching their history (and you have taken a Family Finder or mtDNA test).

What test to take

If your surname is Cleary or one of its variants and you are male, you are encouraged strongly to take a 37 marker Y DNA test to connect with one of the lineages in the Project, or to create a new lineage. 37 markers are the minimum recommended for a useful result, but you may want to consider a higher resolution 111 marker test or Big Y SNP test. As these are more expensive, consult the Project administrators first on how useful doing this may be for your research.

If you are female and want to investigate a Cleary Y line, then you can recruit a close male relative who has the surname, and run a test kit for them. Many members of the Project are running one or more kits for other people as part of their research. It can be your surname too, or maybe the surname of your mother, grandparents or earlier ancestors, but you have an interest in researching this surname line. In this case you can also take the autosomal DNA test Family Finder or upload your autosomal test results from another company. The Project does not show results from autosomal tests on its pages but as a member you can use the Activity Feed to contact other members and publicise your research and family information that you have.

The Ó Cléirigh surnames

Not everyone named Cleary (etc.) today is descended from Irish people who once called themselves Ó Cléirigh in Irish, and it is not a “clan”. But this Irish form of the name is useful to represent all the different names that have descended from it, or have mutated into Cleary-type names over the centuries.

Distribution of Cleary in Ireland, 1901 census

These maps have been created by Barry Griffin who has additional distributions for Cleary from the 1901 and 1911 censuses. There is a search engine at his Surname Maps page from which similar maps for a wide number of Irish surnames can be generated.

The map shows the density of Cleary (this spelling only) across Ireland. Clusters can be picked up around Ballyshannon, Fermanagh and Derry in the north; Mayo and Clare in the west; and a band stretching from Limerick across Tipperary to Kilkenny and Wexford in the south. These are all places historically connected to the Cleary name.

The origins of the Ó Cléirigh surnames

Ó Cléirigh (modern spellings Cleary, Clery, Clary, O’Cleary, O’Clery, O’Clary; can be anglicised as Clarke, Clark)

The classic sources on Irish surname history suggest two origins for this name, one being a derivation of the Irish word cléireach (clerk, cleric, clergyman and by extension priest or scholar), cléirech in Old Irish, cléirigh being the plural form. It is itself derived from the Latin word clericus, the source for a wealth of similar surnames across Europe (e.g. French Clerc, English Clerk, Italian Clerico, Spanish Clerigo). MacLysaght and Woulfe also tell us that the name indicates a descendant of an eponymous 9th century lord in Southern Galway named Cléireach, though as neither of them state that Cléireach was actually a cléireach they seem to be having it both ways.

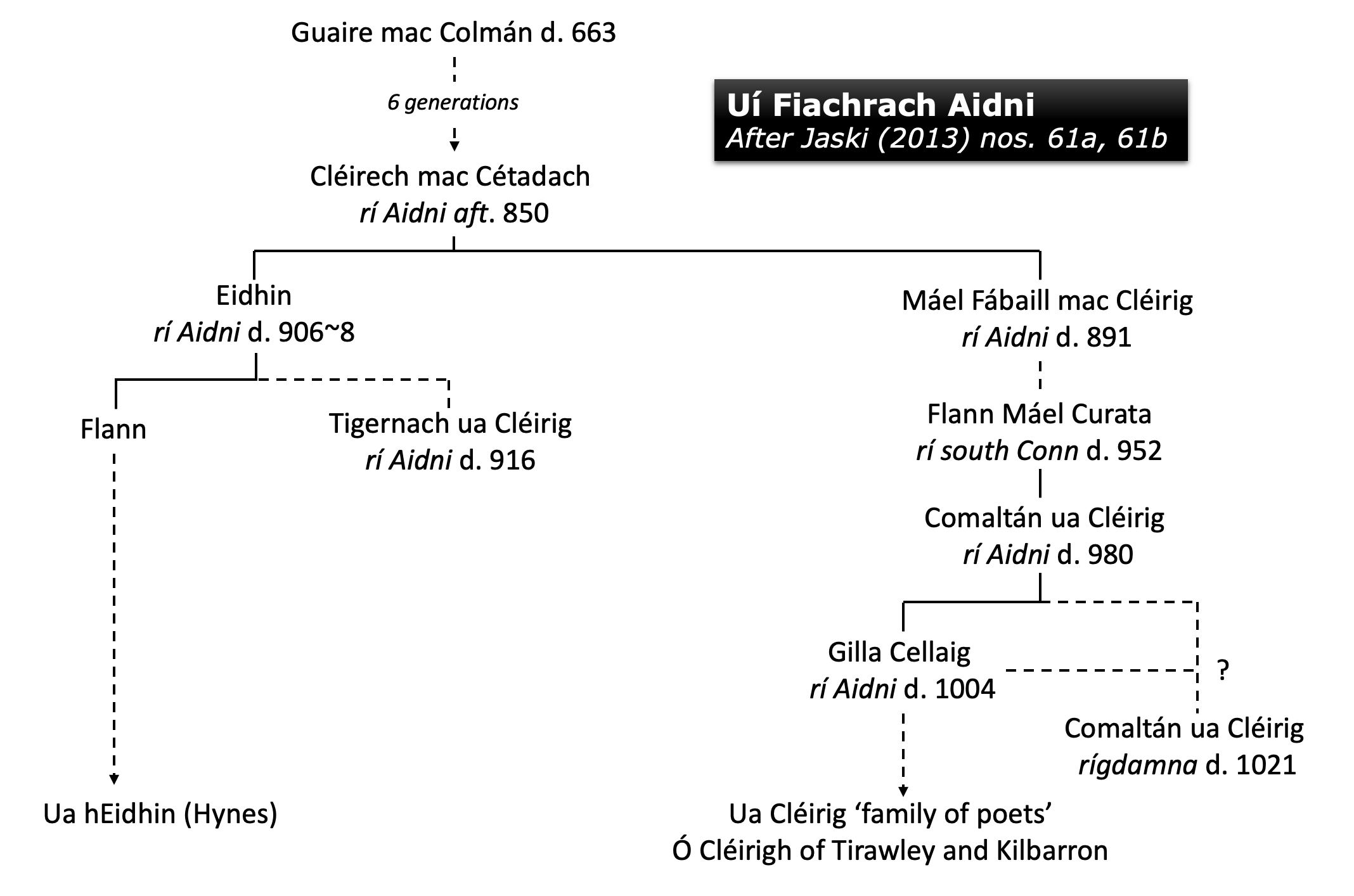

Drawing upon medieval annals and the O Clery Book of Genealogies, Bart Jaski’s Genealogical Tables (2013) show the descent from Cléirech and the adoption of Ua Cléirig as a surname by his descendant in the 3rd or 4th generation, Comaltán (Table 61b, p. 143).

Adrian Martyn (2019, pp. 58-64) argues that Mac and Ó bynames were used to indicate family relationships, but it is only when an Ó name is perpetuated into the 3rd generation and beyond that it is truly being used as a surname. He makes a slight change to Jaski’s tree (see image below) to show Comaltán as the 4th generation descendant of Cléirech making Ó Cléirigh a true dynastic surname from this point on – the oldest on record in Ireland and medieval Europe.

According to the Annals and O Clery Genealogies, Cléirech and his descendants were of the dynasty Uí Fiachrach Aidhni, descendants of the 7th century king of Aidhne and over-king of Connacht, Guaire, who featured in medieval sagas and in WB Yeats’ poem The Three Beggars:

King Guaire walked amid his court

The palace-yard and river-side

And there to three old beggars said,

"You that have wandered far and wide

Can ravel out what's in my head.

Do men who least desire get most,

Or get the most who most desire?'

A beggar said, "They get the most

Whom man or devil cannot tire,

And what could make their muscles taut

Unless desire had made them so?'

But Guaire laughed with secret thought,

"If that be true as it seems true,

One of you three is a rich man,

For he shall have a thousand pounds

Who is first asleep, if but he can

Sleep before the third noon sounds."

And thereon, merry as a bird

With his old thoughts, King Guaire went

From river-side and palace-yard

And left them to their argument.

The palace-yard and river-side

And there to three old beggars said,

"You that have wandered far and wide

Can ravel out what's in my head.

Do men who least desire get most,

Or get the most who most desire?'

A beggar said, "They get the most

Whom man or devil cannot tire,

And what could make their muscles taut

Unless desire had made them so?'

But Guaire laughed with secret thought,

"If that be true as it seems true,

One of you three is a rich man,

For he shall have a thousand pounds

Who is first asleep, if but he can

Sleep before the third noon sounds."

And thereon, merry as a bird

With his old thoughts, King Guaire went

From river-side and palace-yard

And left them to their argument.

Above, Ancient provinces and túath of Ireland - Uí Fiachrach Aidhni can be seen to the east of Galway Bay (Wikimedia Commons, redrawn from Duffy's Atlas of Irish History). Below, the ancient monastery and round tower of Kilmacduagh, a medieval diocese approximately equivalent to Aidhne (Wikimedia Commons CC4.0 licence).

Bearers of the surname Hynes (Ó hEidhin) are also said to be patrilineal descendants of Guaire and Uí Fiachrach Aidhni, and a Y DNA project can investigate this. Comaltán Ua Cléirig, great-grandson or great-great-grandson of Cléirech, was rí (king) in Aidhne – a túath around Gort, south Galway, largely equivalent to the medieval diocese of Kilmacduagh – in the late 10th century. Kilmacduagh is the site of an ancient 7th century monastery which could offer an explanation for the name origins of Cléirech and his dynasty.

Tree showing the descent of Uí Cléirigh from Guaire and the Uí Fiachrach Aidhni according to the medieval Irish Annals, following the genealogies constructed by Bart Jaski. Martyn splits Flann Máel Curata into two persons, father and son. There is some support for this by the long generation interval between them, and the entry in the Annals of the Four Masters which states "920. Mael-micduach, lord of Aidhne, was slain by the foreigners."

According to Woulfe and MacLysaght, the Uí Cléirigh lost their power in Aidhne, and were driven out of Connacht in the late 13th century with three branches settling in Tirawley, Mayo, Co Cavan and Co Kilkenny. The Tirawley branch later settled in Tirconnell (Donegal) and became poets and shanachie to the O’Donnells with a base at Kilbarron Castle, near Ballyshannon. From them descended the famous annalists of the Four Masters, Micheál Ó Cléirigh (1590-1643) and Cú Choigcríche Ó Cléirigh, and their relative Lughaidh Ó Cléirigh, the biographer of Red Hugh O’Donnell. Many Clearys today, especially in the north of Ireland or Kilkenny, could lay claim to descent from this old sept, but not all – the surname is very widely spread across Ireland, and the DNA Project Results table shows that there are many unrelated genetic families who carry one of the Ó Cléirigh names.

de Cléir (modern spellings Clare, Clear, Cleare, Cleere; also de Clare and le Clere; may have merged with Ó Cléirigh in places)

Anglo-Norman name associated with the dynasty of Richard de Clare, 2nd earl of Pembroke and invader of Ireland, known to history as “Strongbow”. MacLysaght states the name was prominent in Wexford, Kilkenny and South Tipperary until the late 17th century (MIF, p. 55), after which it largely merged into the similar but more Gaelic sounding Cleary.

Ó Cléireacháin, Ó Cléirchin (modern spelling Clerihan, O’Clerihan, possibly also Clerian, O’Clerian; anglicised to Clerkin, Clarkin; may have merged with Ó Cléirigh in places, and may also have been anglicised to Clarke, Clark etc.)

Also derived from the diminutive of cléireach or the ‘little clerk’ (Woulfe), linked to Limerick (MacLysaght) and Meath (Woulfe). MacLysaght states that Clerian in Co Monaghan has a different origin to Clerihan, though both could have been derived from Ó Cléireacháin (SOI, p. 48).

Mac an Chléirigh, Mac a’Chléirich (modern forms McCleary, McLeary, McAlary, McClary, McClair, Clark)

Irish or Scottish Gaelic ‘son of the cleric’. More common in Scotland, with various modern forms, and in Ireland likely to have merged with Cleary, O’Clery (FANBI).

Mac Giolla Arraith (modern forms McAlary, Callary, Gallery; can merge with McCleary, McLeary, McClary)

According to FANBI, ‘son of Giolla Arráith’, glossed as a personal name (entry for McAlary) or meaning either son of ‘servant of Arráith’ or Mac Giolla an Ráith, ‘son of the prosperous youth’ (entry for McCleary). Connected with Sligo and Antrim, and may too have merged into Cleary or Clarke in many cases (FANBI).

Clarke, Clark, Clerk, Clerke, Clerc

Recognised by Woulfe and MacLysaght as common anglicised forms in Ireland of all variants of Ó Cléirigh surnames. MacLysaght found that Clarke was the 32nd most common name in Ireland with 14,000 carriers compared with just 5,000 variants of Cleary (IF p. 80), but recognised that this included descendants of Scots and English whose names were originally Clarke. He commented that it was particularly common in Ulster for Ó Cléirigh to be anglicised to Clarke and concluded “Without a reliable pedigree or at least a strong family tradition it is therefore impossible to say whether an Irish Clarke is an O’Clery in disguise or the descendent of an English settler; but it is probable that most of our Clarkes are in fact O’Clerys.” (IF p. 80).

Sources on Irish family names and Ó Cléirigh origins and history

Rev. Patrick Woulfe, Irish Names and Surnames (1923) https://www.libraryireland.com/names/oc/o-clerigh.php &

Some Anglicised Surnames in Ireland (1923) https://www.libraryireland.com/AnglicisedSurnames/Clarke.php (searchable database versions from the National Library of Ireland)

Some Anglicised Surnames in Ireland (1923) https://www.libraryireland.com/AnglicisedSurnames/Clarke.php (searchable database versions from the National Library of Ireland)

Edward MacLysaght The Surnames of Ireland (SOI – 1969 edition, at The Internet Archive)

Irish Families (IF – 1978 edition, at The Internet Archive)

More Irish Families (MIF – 1960 edition, at The Internet Archive)

Patrick Hanks, Richard Coates and Peter McClure. The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland (FANBI, 2016). Online searchable, may be available via your local library at https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199677764.001.0001/acref-9780199677764

Barry Griffin’s Census Surname Maps

Adrian Martyn, Irish Surnames – Origins and Development (2019, www.adrianmartyn.ie )

Bart Jaski, Genealogical Tables of Medieval Irish Royal Dynasties (2013, at Researchgate)

Séamus Pender (ed.), The O Clery Book of Genealogies (RIA 23 D 17), Analecta Hibernica (1951, at JSTOR)

Transcriptions of some of the medieval Irish Annals can be found at The O'Brien Clan History

Paul Walsh, The Clerys of Tirconnell, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review (1935, at JSTOR)